What Was Muir's Theory About The Creation Of Yosemite Valley?

Detail Author:

- Name : Dr. Brant Lehner

- Username : grant.rowe

- Email : crist.vallie@gmail.com

- Birthdate : 1999-04-08

- Address : 639 Swaniawski Station Rueckerville, MT 79105

- Phone : +1 (479) 627-7005

- Company : DuBuque PLC

- Job : Weapons Specialists

- Bio : Inventore vel laudantium officia esse quis aut ullam. Officiis corporis sed aut accusantium.

Socials

linkedin:

- url : https://linkedin.com/in/mekhi_schneider

- username : mekhi_schneider

- bio : Aut rerum quo eum dolor qui.

- followers : 5500

- following : 2696

facebook:

- url : https://facebook.com/mekhi_schneider

- username : mekhi_schneider

- bio : Cupiditate eaque porro et est fuga consequatur molestias accusantium.

- followers : 1390

- following : 2941

twitter:

- url : https://twitter.com/schneider2018

- username : schneider2018

- bio : Harum ea quis sint quibusdam est. Doloribus suscipit adipisci voluptatem aut ad deserunt non. Quia consequatur cumque quisquam molestiae occaecati est.

- followers : 2518

- following : 1338

tiktok:

- url : https://tiktok.com/@mekhi_schneider

- username : mekhi_schneider

- bio : Sit qui quibusdam dolores ratione magnam dolores.

- followers : 1150

- following : 52

Have you ever stood in Yosemite Valley, gazing up at those incredible, towering rock faces, and wondered just how such a magnificent place came to be? It's a question that has puzzled people for ages, and for a very good reason, too. This truly breathtaking spot in California, known for its stunning rock formations and peaceful feel, has a story of creation that's as grand as the valley itself. For many years, people held onto ideas about its beginnings that, well, were a bit different from what we know today. It's almost like the valley held a secret, just waiting for someone special to uncover it.

Long before John Muir arrived on the scene, there were some pretty widely accepted ideas about how Yosemite Valley was shaped. California's first geologists, for instance, had a strong belief. They thought Yosemite was created by a rather dramatic event: a cataclysmic dropping of the valley floor, caused by violent earthquakes. This idea, in some respects, painted a picture of sudden, earth-shattering changes, making it seem as though the valley just appeared almost overnight.

Yet, a different perspective was on its way, one that would change how we view this natural wonder. John Muir, a person deeply connected to the wild places, would eventually challenge these established views. He brought a fresh pair of eyes and a deep love for the land, which, in a way, helped him see something others had missed. His theory, quite bold for its time, would shift the focus from sudden crashes to a slow, powerful force that worked over vast stretches of time.

Table of Contents

- John Muir: A Brief Look

- Early Thoughts on Yosemite's Making

- Muir's Arrival and His Groundbreaking Idea

- The Power of Ice: Muir's Glacial Theory

- Challenging the Established Views

- How Muir's Ideas Took Hold

- Muir's Lasting Influence on Yosemite

- Frequently Asked Questions About Yosemite's Creation

John Muir: A Brief Look

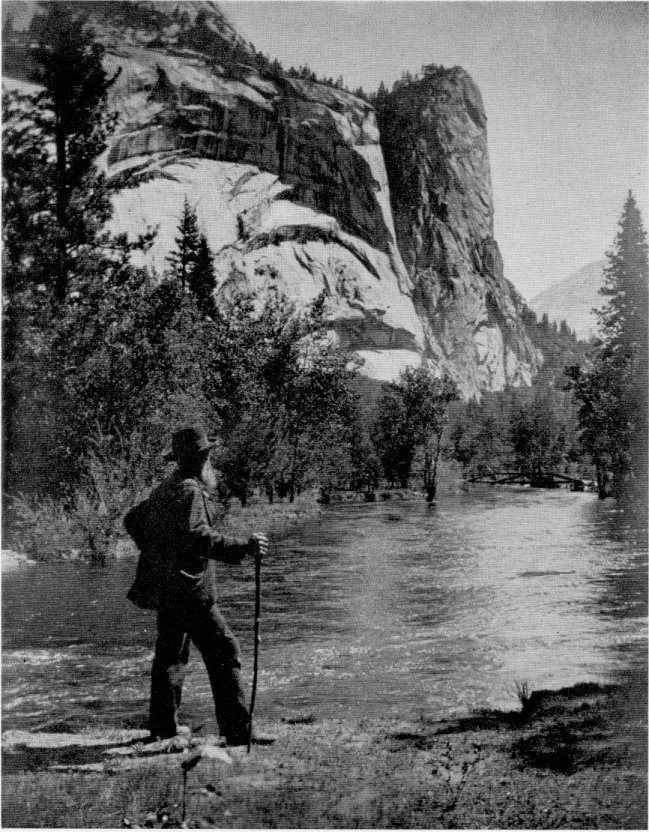

John Muir, a truly significant figure in the story of America's wild places, came to California in the early spring of 1868. He was, you know, a profound advocate for wilderness preservation, and his connection to the Sierra Nevada mountains, especially Yosemite Valley, was deeply personal. He felt a spiritual bond with these grand landscapes, which, in a way, fueled his passion for understanding and protecting them.

In 1870, the very next year after his arrival, Muir actually lived right in Yosemite Valley. He spent his time doing a couple of interesting things: running James Hutching's sawmill and, you know, guiding visitors to the scenic attractions. This gave him a chance to really get to know the land, to explore it deeply, and to conduct his own botanical and geological studies. It was this firsthand experience, in fact, that set the stage for his remarkable insights into the valley's origins.

Personal Details of John Muir (as per "My Text")

| Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Arrival in California | Early spring of 1868 |

| Year Lived in Yosemite Valley | 1870 |

| Activities in Yosemite | Ran James Hutching's sawmill, guided tourists to scenic attractions |

| Key Role | Profound advocate for wilderness preservation |

| Connection to Nature | Felt a spiritual connection to Yosemite Valley and the Sierra Nevada mountains |

| Main Contribution | Demonstrated Whitney’s theory about Yosemite’s formation was in error; advanced glacier theory |

Early Thoughts on Yosemite's Making

Before Muir arrived, the way people thought about Yosemite Valley's creation was, shall we say, a bit different. Early geologists, for instance, held a particular view. They believed that this amazing valley was created by a series of powerful earthquakes that literally sank the valley floor. It was a rather dramatic picture, painting the scene as one of sudden, crushing forces at work.

One widely believed explanation, prior to 1913, was that a large block of the earth's crust had simply down-faulted, creating the valley. This idea, you know, suggested a quick, almost instant formation through massive geological shifts. It was the prevailing wisdom, really, that Yosemite was a result of cataclysmic dropping of the valley floor through violent earthquakes. This was the "exceptional creation theory" that concerned Muir quite a bit, as he saw people being captured by it.

There were, apparently, some twelve theories floating around explaining the origin of Yosemite Valley before 1913. But the earthquake theory, with its vision of sudden collapse, was a very popular one. It seemed to fit the dramatic scale of the valley, in a way, even if it didn't quite capture the true, slow power that actually shaped it. This was the kind of thinking Muir would later challenge, based on his own careful observations.

Muir's Arrival and His Groundbreaking Idea

When John Muir arrived in California in the early spring of 1868, he wasn't just there to admire the views. He was a keen observer, and as a matter of fact, he quickly began to explore the land around Yosemite. He spent his spare time conducting detailed botanical and geological studies, which, you know, meant he was really getting his hands dirty, looking at the rocks and the plants with great care.

Muir, after examining the land very closely, came to a rather different conclusion than the geologists who came before him. He doubted that the valley had been created solely by earthquakes. His studies, basically, led him to believe something quite different. He concluded that glaciers had been the main agent for shaping the valley. This was, arguably, a pretty radical idea at the time, going against what many respected scientists believed.

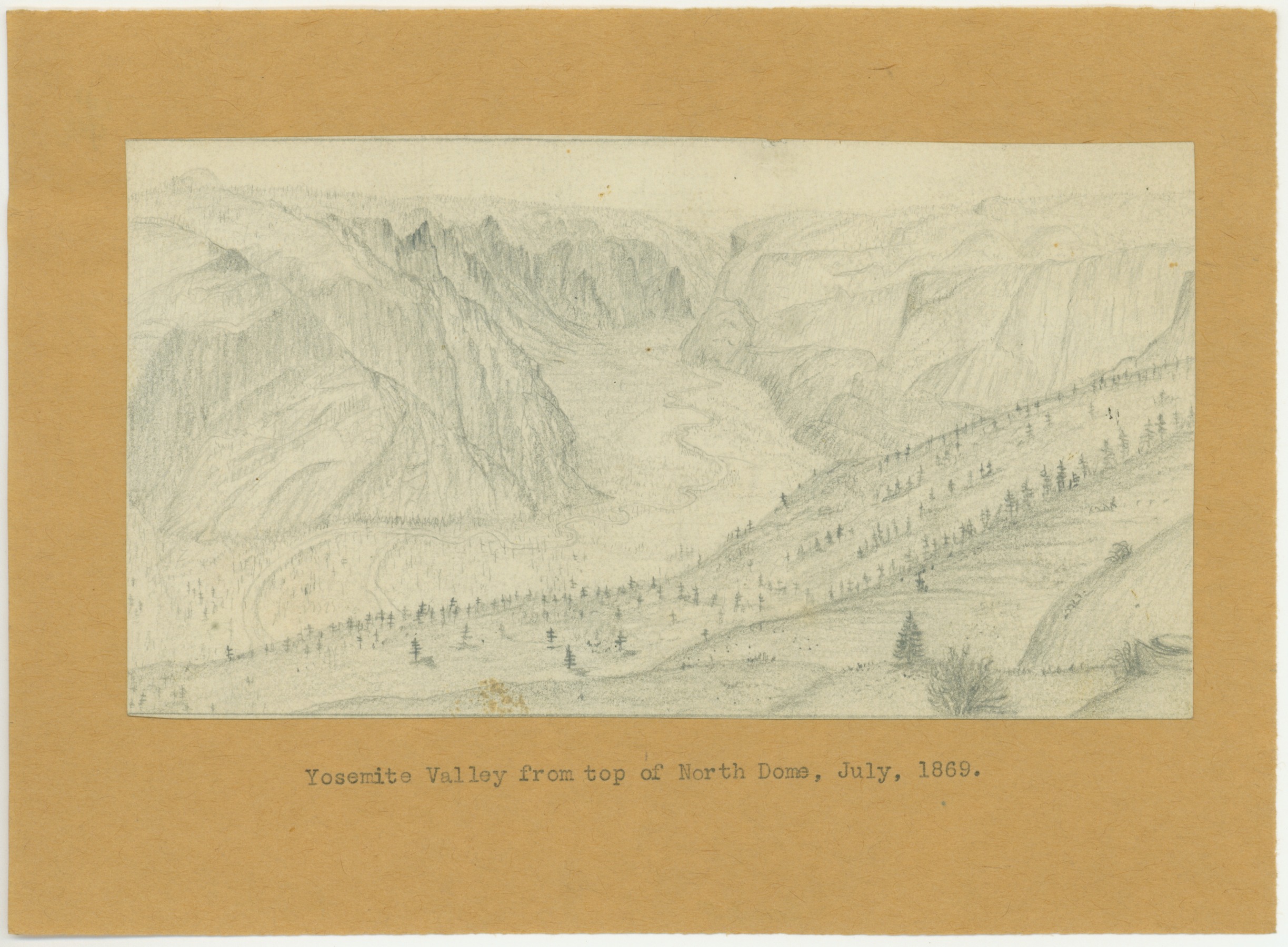

He boldly advanced this unorthodox idea: that Yosemite had been gouged out primarily by a mighty glacier of the ice age. And not only that, but it had been elaborated little by little over a long period. This was a completely new way of thinking about the valley's formation, suggesting a process of slow, relentless carving rather than a sudden, dramatic drop. It was a theory born from his deep personal connection to the land and his careful scientific observations.

The Power of Ice: Muir's Glacial Theory

Muir's core idea, the one that really set him apart, was about the immense power of ice. He rightfully concluded that Yosemite had been carved not by a sudden collapse, but by the slow, powerful grind of immense amounts of ice. This was a truly profound insight, seeing the valley as a product of a patient, persistent force rather than a quick, violent one. It's almost like he saw the valley breathing, changing over eons.

He described glaciers as essentially rivers of ice. Imagine, if you will, these massive, slow-moving rivers, hundreds of feet thick, creeping down the mountain slopes. These rivers of ice, as Muir saw them, had the incredible ability to scrape, polish, and shape the hard granite. They could, you know, pick up rocks and use them as tools, grinding away at the valley floor and sides, little by little, over countless years.

This theory meant that the grand, U-shaped cross-section of Yosemite Valley, with its sheer cliffs and wide floor, was a signature of glacial erosion. All of the valleys of both genera, he argued, are valleys of erosion. In his description of the Merced Yosemite Valley, Muir discusses this exceptional creation theory, emphasizing its errors. He was, quite frankly, very confident in what he saw and understood.

Challenging the Established Views

Muir's theory was, in a way, a direct challenge to the prevailing scientific thought of his time. Before Muir arrived, as we know, California's first geologists, like Josiah Whitney, had theorized that Yosemite was created by a cataclysmic dropping of the valley floor through violent earthquakes. Whitney's theory was very popular, and many people, you know, pilgrims visiting Yosemite, were captured by it, regarding it as the absolute truth.

What concerned Muir most at this time was the ease with which bands of Yosemite pilgrims were captured by Whitney’s exceptional creation theory of the valley’s origin. He saw that this theory led people to regard the valley in a certain way, perhaps missing the deeper, more gradual story of its making. Muir, based on his studies, had a different perspective, and he wasn't afraid to share it, even if it meant going against the grain.

John Muir was mainly responsible for demonstrating that Whitney’s theory about the formation of Yosemite Valley was in error and untenable. This wasn't just a minor disagreement; it was a fundamental shift in understanding. He presented his case with such conviction and evidence that, eventually, others began to listen. This was, you know, a huge step for how geology was understood in the region.

How Muir's Ideas Took Hold

Muir's relentless exploration and careful observations eventually started to sway other prominent scientists. For example, Leconte, another respected figure, agreed with the naturalist’s theory that a river of ice, in part, shaped Yosemite’s mountains. This agreement from a peer was, you know, a significant step in gaining wider acceptance for Muir's ideas. It showed that his "unorthodox" theory had merit and was based on solid evidence.

In short, as Muir himself might have put it, we are led irresistibly to the adoption of a theory of the origin of Yosemite in a way which has hardly yet been recognized as one of those in which valleys may be formed. This suggests that Muir wasn't just offering an alternative; he was proposing a whole new framework for understanding how such valleys could be created. His insights were, arguably, ahead of their time, showing a process that was previously overlooked.

His detailed studies and his ability to communicate his findings, both through scientific observation and his famous poetic imagery, helped his theory gain traction. He inspired Yosemite’s travelers to see under the surface, to look beyond the obvious. It was through his eyes, you know, that people began to appreciate the slow, powerful forces that truly shaped this incredible place. This shift in perspective was, in a way, a quiet revolution.

Muir's Lasting Influence on Yosemite

John Muir's impact on how we understand and appreciate Yosemite Valley goes far beyond just geology. His poetic reflections have inspired generations to see Yosemite’s grandeur beyond its surface. He famously encouraged people to "climb the mountains and get their good tidings," promising that "Nature’s peace will flow into" them. This kind of language, you know, made his scientific observations feel deeply personal and accessible.

Muir, a profound advocate for wilderness preservation, emphasized the unique features of both the Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy valleys, both known for their breathtaking rock formations. He wasn't just interested in how they were made, but also in why they mattered and why they needed to be protected. His geological insights, in a way, underpinned his passionate calls for conservation, giving them a scientific foundation.

Today, the understanding that glaciers played a primary role in carving Yosemite Valley is widely accepted, thanks in large part to Muir's groundbreaking work. He showed us that the valley, which is Miwok for "killer," is indeed a glacial valley in Yosemite National Park, located in the western Sierra Nevada mountains of central California. His legacy lives on, inspiring people to look closely at nature and to understand its deep, powerful stories. To learn more about John Muir's life and work on our site, you can visit this page exploring the Sierra Nevada's geological wonders.

Frequently Asked Questions About Yosemite's Creation

What did geologists think about Yosemite's formation before John Muir?

Before John Muir, many geologists, including California's first geologists, believed that Yosemite Valley was created by a series of powerful earthquakes. They thought these seismic events caused the valley floor to sink dramatically, creating the deep, impressive chasm we see today. It was, you know, a theory of sudden, cataclysmic changes, rather than a slow, gradual process.

How did John Muir come to his glacier theory for Yosemite?

John Muir arrived in California in 1868 and, in 1870, lived in Yosemite Valley, dividing his time between running a sawmill and guiding tourists. He spent his spare time exploring the land and conducting his own botanical and geological studies. It was through these direct observations and examinations of the land that he concluded glaciers had been the main agent, seeing evidence of their slow, powerful grind, which, in a way, contrasted sharply with the earthquake theory.

Who supported Muir's ideas about Yosemite's formation?

While Muir's ideas were initially unorthodox, he did gain support from other scientists. For instance, Leconte, another notable figure, agreed with Muir's theory that a river of ice, in part, shaped Yosemite’s mountains. This agreement from respected peers helped to validate Muir's groundbreaking observations and helped his theory gain more acceptance over time, showing that his insights were, you know, truly convincing.